The Law in Alabama

Brenda Wilson Wooley

It was deep summer in the Deep South. World War II had finally come to an end and everyone was optimistic, looking forward to the future. But ten-year-old Billy Wooley wasn’t interested in world affairs; he had other things on his mind.

Billy lived with his father and grandmother, Big Momma, in Cottondale, Alabama, a small, sleepy town near Tuscaloosa. He knew everyone, and everyone knew him, so he was on his own that summer, exploring the hills and hollows of Alabama, fishing, catching grasshoppers.

He sometimes ventured deep into the woods and picked up kindling, which he loaded on his little red wagon and pulled into town. He sold it for a fraction of what it was worth, hoping to earn enough to go to The Bama in Tuscaloosa on Saturday afternoons to see Gene Autry or Roy Rogers. Sometimes, he had enough for a bag of popcorn.

After the picture show, Billy generally meandered around, seeing what was going on, listening to the latest gossip. And one subject that came up time and again was “The Klan.” The old men in the town square talked about them; his papa and uncles talked about them. Even his mother and her friends mentioned them from time to time.

“They got after Luther Perkins the other night,” Uncle Dee told Billy’s papa one Saturday afternoon. They were leaning against Uncle Dee’s Nash, sipping moonshine.

“It’s about time,” Papa said, “He’s been beatin’ up on his old lady for years.”

“Well, they warned him before,” Uncle Dee said, “So he got what he deserved.”

“Yep, the Klan don’t give second chances. They’re the law in Alabama.”

Billy was curious. He wanted to know more about the law in Alabama. And a few months later, he found out much more than he wanted to know.

It was a hot, humid night, and Papa was sitting on the front porch with Big Momma, who was patching socks. Billy had been catching lightening bugs, but he had gotten tired of that. He had just plopped down on the steps, when a line of car lights rounded the curve, one right behind the other, moving very slowly.

Big Momma leaned forward, huge breasts dragging across her lap. “Wonder what’s going on?”

“Hard telling,” said Papa.

Billy counted the big black cars as they crawled past the house. There were eleven.

Papa craned his neck. “They’re turning in at the school house. Must be something to do with that colored man they think killed that white boy down there.”

Billy glanced at Papa and Big Momma. They were settling back in their rockers and talking about something else, so he slipped inside the front door and raced through the house and out the back door.

He took off down the hollow to the railroad tracks. As he crisscrossed through the woods, he could hear the loud chant of the katydids, bull frogs croaking in the nearby swamps, unknown creatures scuttling through the underbrush.

As he neared the edge of the woods behind the schoolhouse, he could see flickering shadows of the men as they got out of their cars and passed in front of the car lights. And a low murmuring sound.

He pulled the bushes back, swatting at mosquitoes swarming around his face, and froze. They were all dressed in white and wearing tall pointed hats, hoods covering their faces. Several were carrying a big cross. The rest were forming a circle.

The low murmuring started again, reminding him of Sunday morning services at church with Big Momma, just before the Holy Spirit grabbed hold of people, threw them to the floor, caused them to speak in unknown tongues.

Chills rushed up and down Billy’s back as he watched the men drag the big cross to the center of the schoolyard. All in white, faces hooded, they looked like ghosts.

They stood quietly for a moment, and then one man stepped forward and struck a match, tossing it on the big cross. Swoosh! Billy jumped back as the whole school yard lit up.

A Klansman walked out of the shadows. He was leading a young colored man, and the look on his face was one of sheer terror.

The Klansman led the man to the burning cross. “Kneel!” he yelled, “And pray!”

The man knelt, placed the palms of his hands together, and bowed his head.

All was quiet for a moment, and then the Klansman motioned to him, “Now, get up!”

The man got up, but as the Klansman started to grab his arm, he jerked away and took off. Billy had never seen anyone run as fast in his life. He was heading toward the woods, directly where Billy was crouching, and before he could move, the man was facing him. He hesitated, his eyes holding Billy’s for a second, and then he was gone.

Billy cringed, waiting for the Klansmen to come after the man, but they huddled again, the murmuring continuing. Some lit cigarettes. And one looked toward the spot where Billy was hiding. He crouched lower, flinching as something slithered across his bare feet.

Finally, they all got into their cars and slowly drove away.

As soon as they were out of sight, Billy sprinted through the woods at breakneck speed, dashing into the kitchen just as Papa and Big Momma were coming through the front door.

“Get them feet washed and go ahead on to bed,” Big Momma said.

In bed, Billy couldn’t quit thinking about the young colored man. He hoped the Klan wouldn’t hunt him down. They weren´t supposed to. The sheriff was supposed to find out who killed that boy, and then they were supposed to have a trial.

He had learned that in school.

“Everyone is innocent until proven guilty,” Miss Iris said, “No one can take the law into their own hands.”

Afterward, they had a mock trial, and Billy was on the jury.

Billy tried to put the incident out of his mind, but a few days later he heard them talking about it again.

“The sheriff got that man that killed that boy over at the school,” Papa told Big Momma, “He wasn’t from around here.”

Billy was glad. But he couldn’t get the young man’s face out of his mind, the helplessness and fear in his eyes. It reminded him of the day he came upon the neighbor’s dogs chasing a stray kitten. He had grabbed the kitten just in time. It was trembling, defenseless. Just like the young colored man.

Billy wished he hadn´t gone to the school yard that night, never seen the Klan. But one Sunday night, a few weeks later, he saw them again.

He and Big Momma were in church, and services were almost over. The pastor was preparing to lead the closing prayer when the church doors burst open and a Klansman appeared. He was carrying a battery-powered cross; it blinked like Christmas tree lights. Behind him were several more, all dressed in white and wearing hoods.

The preacher stopped talking, and the congregation was quiet as they watched them march down the aisle of the little church. When they got to the pulpit, they stopped, and then the leader marched to the collection place and dropped in a wad of bills. Without saying a word, they marched back down the aisle and out of the church.

The pastor raised his hands in the air. “God bless them for their very generous donation,” he said, "Now, let´s pray."

As the pastor gave the closing prayer, Billy thought about the young man, scared and helpless. Why should God bless the Klan? They were worse than those dogs, chasing the defenseless cat. And no matter what Papa had said, Billy knew they were not the law in Alabama.

...............

Note from the author:

"The Law in Alabama" is an excerpt from my husband's memoirs, which I'm working on. Bill picked cotton alongside blacks in Alabama, Mississippi and Arkansas, so he learned first hand the injustices they faced. They sang gospel songs after those long work days were over, and he vividly recalls the sound of their melodious voices wafting across the fields at twilight. "They were good, kind people," he said, "so I could never understand why the Klan was so intent on making their lives a living hell."

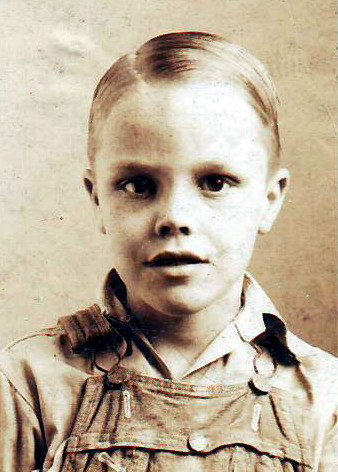

Bill: