Naming Stars

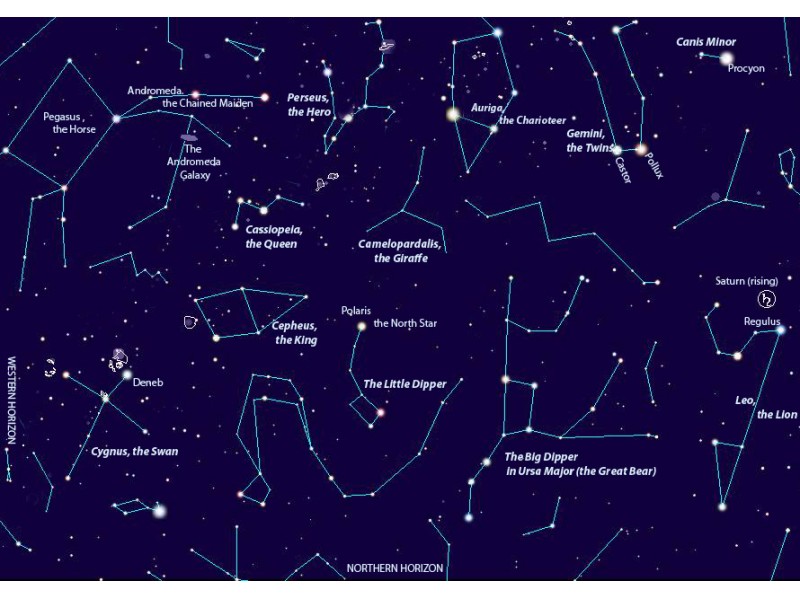

Constellations are the locations for stars. The brighter stars have traditional names and Bayer designations, while others have only catalog numbers.

How many stars can you name? Do you think a professional astronomer would do better — or about the same?

Too many to remember

We can all name at least one star — Earth's daytime star in our own language! That's the Sun in English. It gets harder after the Sun sets, and the dark sky reveals Sirius, Betelgeuse, Polaris, Arcturus or Vega. These are the common names of some bright stars, but with the unaided eye you might see a few thousand stars from a dark location.

Of course, more stars are visible with a telescope, the bigger the better. The Hubble Space Telescope Guide Star Catalog lists 19 million dim stars. There wouldn't be time to give them all unique names, let alone learn them.

As it happens, astronomers don't name stars. In addition, most professionals rarely use star names, because it isn't useful for their work. That means you could well know just as many star names as the professionals, probably more.

Stars and constellations

There are a few hundred individual star names, almost all coming to us from the Arabs and the Greeks of many centuries ago. They named bright stars or members of prominent constellations and asterisms. An asterism is a pattern of stars that's part of one or more constellations.

In fact it's the groups of stars that have always been the key to knowing the sky. Even a star's name often refers to its place in a constellation. For example, Rigel in Orion is the hunter's left foot. The name just means foot. The star Alpha Centauri is also known as Rigil Kentaurus, the Centaur's foot.

Constellations have changed over millennia and from culture to culture, but are a feature of astronomy throughout history. People could learn to recognize groups of stars, and let the sky serve as a clock or calendar or navigation aid. Learning a thousand star names would be like memorizing a thousand phone numbers.

Bayer and Flamsteed

If giving each star a name isn't practical, then you need a naming system. In 1603 German astronomer Johann Bayer (1572-1625) published a star atlas using Greek letters for the stars in a constellation, usually grouping them into classes of brightness. Often the alpha star is the brightest, but the stars aren't in brightness order within each class.

In fact, Bayer wasn't consistent in how he labelled the stars, and sometimes it's hard to tell what he had in mind. For example, Alpha Centauri is the brightest star in Centaurus, but Alpha Sagittarii is the 16th brightest in Sagittarius. You'll notice that the form of the constellation name isn't the familiar one. Bayer used the Latin possessive form of the name, so Alpha Centauri means "alpha of Centaurus”.

Since constellations may have more stars than the Greek alphabet does letters, Bayer also used letters from the Latin alphabet — the one we use — if needed. The invention of the telescope meant more stars to account for, so the Bayer system became even more limited. However it's still in use, as you can see in this star map of southern constellations.

Another way of identifying stars is by using catalog numbers. The catalogs have changed, but not the idea. The star atlas of John Flamsteed (1646-1719) was the first major one to be based on telescopic observations, and it was the most authoritative one available for many decades. The numbers however were added to the catalog later by French astronomer Joseph Jerome de Lalande (1782-1807).

Flamsteed numbers are used for stars without a Bayer designation. They follow the same pattern, but numbers replace Greek letters. A famous example is 51 Pegasi, which is the first Sun-like star found to have a planet orbiting it.

Henry Draper and beyond

Often we see stars identified by an HD number. Betelgeuse, for example, is HD 39801, but stars without distinct names are the ones most likely to be shown in this way. HD refers to the Henry Draper catalog. A number of star catalogs bear the name of the compiler, but not this one. Although Draper planned a catalog with stars classified by their spectra, he died before his project really got going. Henry Draper's widow gave the money to Harvard College Observatory to carry out the project. The catalog contains spectra of over a quarter of a million stars, most of the work done by Annie Cannon.

The large sky survey projects of today generate catalogs by computer, with the stars identified by their positions in the sky at a particular time.

What the IAU does

The International Astronomical Union (IAU) is in charge of standards for naming heavenly bodies. The naming and monitoring of minor planets requires considerable oversight, but since stars aren't named, there isn't much to do in that regard. The IAU did however tidy up the constellations. In 1922 the entire sky was divided up into 88 clearly-defined constellations.

With regard to star names, the IAU does maintain a database of catalogs. Each new catalog gets a unique designation of initial letters, to ensure that the stars are identified unambiguously.

Can you name a star?

The simple answer is: Yes. You can name a star anything you like, make a certificate for yourself, put it on your Facebook page and tweet it to all your followers. And, at no cost, your star name will have as much official standing as the ones you can buy from commercial companies, i.e., none.

It's not illegal to name stars or to charge for doing it. However the seller mustn't say (or imply) that any name will be officially recognized, because the IAU does not sanction this.

How many stars can you name? Do you think a professional astronomer would do better — or about the same?

Too many to remember

We can all name at least one star — Earth's daytime star in our own language! That's the Sun in English. It gets harder after the Sun sets, and the dark sky reveals Sirius, Betelgeuse, Polaris, Arcturus or Vega. These are the common names of some bright stars, but with the unaided eye you might see a few thousand stars from a dark location.

Of course, more stars are visible with a telescope, the bigger the better. The Hubble Space Telescope Guide Star Catalog lists 19 million dim stars. There wouldn't be time to give them all unique names, let alone learn them.

As it happens, astronomers don't name stars. In addition, most professionals rarely use star names, because it isn't useful for their work. That means you could well know just as many star names as the professionals, probably more.

Stars and constellations

There are a few hundred individual star names, almost all coming to us from the Arabs and the Greeks of many centuries ago. They named bright stars or members of prominent constellations and asterisms. An asterism is a pattern of stars that's part of one or more constellations.

In fact it's the groups of stars that have always been the key to knowing the sky. Even a star's name often refers to its place in a constellation. For example, Rigel in Orion is the hunter's left foot. The name just means foot. The star Alpha Centauri is also known as Rigil Kentaurus, the Centaur's foot.

Constellations have changed over millennia and from culture to culture, but are a feature of astronomy throughout history. People could learn to recognize groups of stars, and let the sky serve as a clock or calendar or navigation aid. Learning a thousand star names would be like memorizing a thousand phone numbers.

Bayer and Flamsteed

If giving each star a name isn't practical, then you need a naming system. In 1603 German astronomer Johann Bayer (1572-1625) published a star atlas using Greek letters for the stars in a constellation, usually grouping them into classes of brightness. Often the alpha star is the brightest, but the stars aren't in brightness order within each class.

In fact, Bayer wasn't consistent in how he labelled the stars, and sometimes it's hard to tell what he had in mind. For example, Alpha Centauri is the brightest star in Centaurus, but Alpha Sagittarii is the 16th brightest in Sagittarius. You'll notice that the form of the constellation name isn't the familiar one. Bayer used the Latin possessive form of the name, so Alpha Centauri means "alpha of Centaurus”.

Since constellations may have more stars than the Greek alphabet does letters, Bayer also used letters from the Latin alphabet — the one we use — if needed. The invention of the telescope meant more stars to account for, so the Bayer system became even more limited. However it's still in use, as you can see in this star map of southern constellations.

Another way of identifying stars is by using catalog numbers. The catalogs have changed, but not the idea. The star atlas of John Flamsteed (1646-1719) was the first major one to be based on telescopic observations, and it was the most authoritative one available for many decades. The numbers however were added to the catalog later by French astronomer Joseph Jerome de Lalande (1782-1807).

Flamsteed numbers are used for stars without a Bayer designation. They follow the same pattern, but numbers replace Greek letters. A famous example is 51 Pegasi, which is the first Sun-like star found to have a planet orbiting it.

Henry Draper and beyond

Often we see stars identified by an HD number. Betelgeuse, for example, is HD 39801, but stars without distinct names are the ones most likely to be shown in this way. HD refers to the Henry Draper catalog. A number of star catalogs bear the name of the compiler, but not this one. Although Draper planned a catalog with stars classified by their spectra, he died before his project really got going. Henry Draper's widow gave the money to Harvard College Observatory to carry out the project. The catalog contains spectra of over a quarter of a million stars, most of the work done by Annie Cannon.

The large sky survey projects of today generate catalogs by computer, with the stars identified by their positions in the sky at a particular time.

What the IAU does

The International Astronomical Union (IAU) is in charge of standards for naming heavenly bodies. The naming and monitoring of minor planets requires considerable oversight, but since stars aren't named, there isn't much to do in that regard. The IAU did however tidy up the constellations. In 1922 the entire sky was divided up into 88 clearly-defined constellations.

With regard to star names, the IAU does maintain a database of catalogs. Each new catalog gets a unique designation of initial letters, to ensure that the stars are identified unambiguously.

Can you name a star?

The simple answer is: Yes. You can name a star anything you like, make a certificate for yourself, put it on your Facebook page and tweet it to all your followers. And, at no cost, your star name will have as much official standing as the ones you can buy from commercial companies, i.e., none.

It's not illegal to name stars or to charge for doing it. However the seller mustn't say (or imply) that any name will be officially recognized, because the IAU does not sanction this.

You Should Also Read:

What Are Constellations

Photography and the Birth of Astrophysics

Annie Jump Cannon

Related Articles

Editor's Picks Articles

Top Ten Articles

Previous Features

Site Map

Content copyright © 2023 by Mona Evans. All rights reserved.

This content was written by Mona Evans. If you wish to use this content in any manner, you need written permission. Contact Mona Evans for details.