The Miracle on the Hudson

“What a view of the Hudson today,” said Captain Sully, and First Officer Jeffrey B. Skiles, who was piloting US Airways Flight 1549, agreed. It was Thursday, January 15, 2009. The plane had just taken off from New York’s LaGuardia Airport and was headed for Charlotte, North Carolina, as usual. From almost 3,000 feet in the air, the river was probably glimmering in the late-afternoon light. Little did the pilots expect an extreme close-up. So why did Flight 1549 land in the Hudson River minutes later?

Because bird strikes.

A bird strike can be a bird ingestion, which may evoke the concept more vividly. The “accident airplane,” as it’s called in the official report, was an Airbus A320 powered by two jet engines. Climbing to an initial altitude, it crossed paths with giant Canada geese, migrants on their own routine flight. Each engine ingested two. Weighing about 8 pounds each, these birds often, though unwittingly, endanger human aviation. As the plane cut through the panicking flock, it shuddered and made sounds “like a tennis shoe thrown into a dryer,” Sully would later say, “only much louder.”

It happened at 3:27, just half a minute after he had marveled at the view. From then on, the cockpit voice recording, which is transcribed in the accident report, reads like a Hollywood screenplay. Sully had even clocked the geese. “Birds,” he said, the second before they struck. Susan O’Donnell, an off-duty pilot hitching a ride on the flight, later described a “stench of burning bird” with the noises. Then a worse sound: engines decelerating. The A320 had lost thrust and would soon start gliding to the ground. Still, the captain was in control and panic had yet to set in. The plane banked left, and O’Donnell assumed they were returning to LaGuardia.

They were. Chesley B. Sullenberger III is not a man of many words, so when the engines failed to restart, he simply said, “My aircraft.” Skiles replied, “Your aircraft.” Actions were going to speak louder that day, anyway. Sully had more experience flying A320s, and both men were tacitly agreeing that Skiles, who had more recently finished the in-service training that pilots must undergo every year, would be quicker with the emergency checklists they now needed to use. As the captain later told Air & Space magazine, while he flew the plane, his first officer kept trying “to restart the engines and hoping that we wouldn’t have to land some place other than a runway.”

Running out of runways

So Sully’s first mayday call informed ground control that the plane was turning back. On Long Island, air-traffic controller Patrick Harten was in charge, and he quickly got LaGuardia to halt their departures. As The New York Times remarked later, the only hint of stress in the ensuing dialogue was both sides’ fumbling of the flight’s call sign. Sully said they were “Cactus 1539,” and Harten called them “Cactus 1529.” The numbers were, like the plane, fast descending. Offered a runway at LaGuardia, the captain replied, “We’re unable. We may end up in the Hudson.”

He too was still hoping to land on a runway – any runway. Yet returning to LaGuardia at less than 300 knots meant flying low over densely populated Manhattan, and Sully didn’t like the odds. Harten, coordinating several other planes, continued to suggest runways as Skiles checked emergency procedures off the first of a three-page list. Meanwhile, the plane went on making noises, its automated sensors chiming and warning of traffic and wind shear and vertical speed. Everyone – everything – was multitasking. Offered another runway, Sully’s response was terse: “Unable.” A second later a sensor went off – they had come too close to a tour helicopter below them. Probably a good thing they didn’t know it then.

Normally, Flight 1549 would fly over Teterboro Airport in New Jersey. It was now no closer than LaGuardia, but maybe it posed fewer constraints. Sully radioed Harten and then addressed his passengers: “This is the captain. Brace for impact.” Through the cockpit door, he later told Air & Space, he heard the cabin crew instruct the passengers, “Brace! Brace! Heads down! Stay down!” and the speed of their response boosted his confidence.

Just as quickly, Harten arranged for a runway at Teterboro. However, the plane had now lost too much altitude to reach it safely. Months later, the transportation safety board’s simulations would vindicate the captain’s instincts. “We can’t do it,” he radioed, and when asked which runway he would like, he said, “We’re gonna be in the Hudson.”

“I’m sorry,” said Harten. “Say again, Cactus?”

But that was it from Cactus 1549. A pilot can’t fly and talk at the same time, especially if he’s making an emergency touchdown. As the first officer tried one last time to relight the engines, another warning system kicked in. “Too low. Terrain. Caution. Terrain. Pull up. Pull up. Pull up.” This chant went on right to the end as Skiles adjusted the landing flaps, Sully eased the plane down, and Harten tried in vain to reestablish contact. In the last few seconds Sully asked, “Got any ideas?” and Skiles replied, “Actually not.”

Then the Hudson became a runway.

Waiting on the wings

By all accounts, Flight 1549 made the perfect landing: wings level, nose up, speed at just above the minimum. The river, though, had sliced through the plane’s rear section and was filling it fast with water. Exiting the cockpit, the pilots gave the order to evacuate, and flight attendants Donna Dent, Doreen Welsh and Sheila Dail organized an orderly evacuation at the front doors and over the wings. Although most didn’t put on their life vests, the passengers helped each other move to the front of the plane and out.

The photo is now iconic: the A320 floating on the water, its passengers and crew members balancing on its wings. The damaged plane itself would end up underwater, but all 155 occupants, including a 9-month-old boy, survived. What a view of the Hudson.

The reality of the aftermath – that some passengers panicked or slipped into the freezing water, or thought they were going to die after surviving the landing – was not captured on cameras or voice recordings. In 2014, a National Geographic film depicted their experience, showing that some were more traumatized than others. The same goes for the crew. When Welsh exited the plane, she realized a metal bar had cut into her leg, and she was bleeding from the mouth because she had bit down on her tongue upon impact. Flight 1549 was her last as a cabin attendant.

Nonetheless, what could have ended in tragedy became a thrilling feel-good story. In 2015, Clint Eastwood started filming the Hollywood version with Tom Hanks as Captain Sully. From bird strike to splashdown, only three and a half minutes had passed, so Sully’s quick thinking and decades of flying were absolutely critical. But more was at work that afternoon. A day later and the river would have been filled with chunks of ice. An hour forward, and they would have had to land in darkness. A less experienced co-pilot and cabin crew, and they might not have acted with such composure or in such balletic concert. Call these things luck, but New York’s then-governor gave it a more enduring name: the Miracle on the Hudson.

Because bird strikes.

A bird strike can be a bird ingestion, which may evoke the concept more vividly. The “accident airplane,” as it’s called in the official report, was an Airbus A320 powered by two jet engines. Climbing to an initial altitude, it crossed paths with giant Canada geese, migrants on their own routine flight. Each engine ingested two. Weighing about 8 pounds each, these birds often, though unwittingly, endanger human aviation. As the plane cut through the panicking flock, it shuddered and made sounds “like a tennis shoe thrown into a dryer,” Sully would later say, “only much louder.”

It happened at 3:27, just half a minute after he had marveled at the view. From then on, the cockpit voice recording, which is transcribed in the accident report, reads like a Hollywood screenplay. Sully had even clocked the geese. “Birds,” he said, the second before they struck. Susan O’Donnell, an off-duty pilot hitching a ride on the flight, later described a “stench of burning bird” with the noises. Then a worse sound: engines decelerating. The A320 had lost thrust and would soon start gliding to the ground. Still, the captain was in control and panic had yet to set in. The plane banked left, and O’Donnell assumed they were returning to LaGuardia.

They were. Chesley B. Sullenberger III is not a man of many words, so when the engines failed to restart, he simply said, “My aircraft.” Skiles replied, “Your aircraft.” Actions were going to speak louder that day, anyway. Sully had more experience flying A320s, and both men were tacitly agreeing that Skiles, who had more recently finished the in-service training that pilots must undergo every year, would be quicker with the emergency checklists they now needed to use. As the captain later told Air & Space magazine, while he flew the plane, his first officer kept trying “to restart the engines and hoping that we wouldn’t have to land some place other than a runway.”

Running out of runways

So Sully’s first mayday call informed ground control that the plane was turning back. On Long Island, air-traffic controller Patrick Harten was in charge, and he quickly got LaGuardia to halt their departures. As The New York Times remarked later, the only hint of stress in the ensuing dialogue was both sides’ fumbling of the flight’s call sign. Sully said they were “Cactus 1539,” and Harten called them “Cactus 1529.” The numbers were, like the plane, fast descending. Offered a runway at LaGuardia, the captain replied, “We’re unable. We may end up in the Hudson.”

He too was still hoping to land on a runway – any runway. Yet returning to LaGuardia at less than 300 knots meant flying low over densely populated Manhattan, and Sully didn’t like the odds. Harten, coordinating several other planes, continued to suggest runways as Skiles checked emergency procedures off the first of a three-page list. Meanwhile, the plane went on making noises, its automated sensors chiming and warning of traffic and wind shear and vertical speed. Everyone – everything – was multitasking. Offered another runway, Sully’s response was terse: “Unable.” A second later a sensor went off – they had come too close to a tour helicopter below them. Probably a good thing they didn’t know it then.

Normally, Flight 1549 would fly over Teterboro Airport in New Jersey. It was now no closer than LaGuardia, but maybe it posed fewer constraints. Sully radioed Harten and then addressed his passengers: “This is the captain. Brace for impact.” Through the cockpit door, he later told Air & Space, he heard the cabin crew instruct the passengers, “Brace! Brace! Heads down! Stay down!” and the speed of their response boosted his confidence.

Just as quickly, Harten arranged for a runway at Teterboro. However, the plane had now lost too much altitude to reach it safely. Months later, the transportation safety board’s simulations would vindicate the captain’s instincts. “We can’t do it,” he radioed, and when asked which runway he would like, he said, “We’re gonna be in the Hudson.”

“I’m sorry,” said Harten. “Say again, Cactus?”

But that was it from Cactus 1549. A pilot can’t fly and talk at the same time, especially if he’s making an emergency touchdown. As the first officer tried one last time to relight the engines, another warning system kicked in. “Too low. Terrain. Caution. Terrain. Pull up. Pull up. Pull up.” This chant went on right to the end as Skiles adjusted the landing flaps, Sully eased the plane down, and Harten tried in vain to reestablish contact. In the last few seconds Sully asked, “Got any ideas?” and Skiles replied, “Actually not.”

Then the Hudson became a runway.

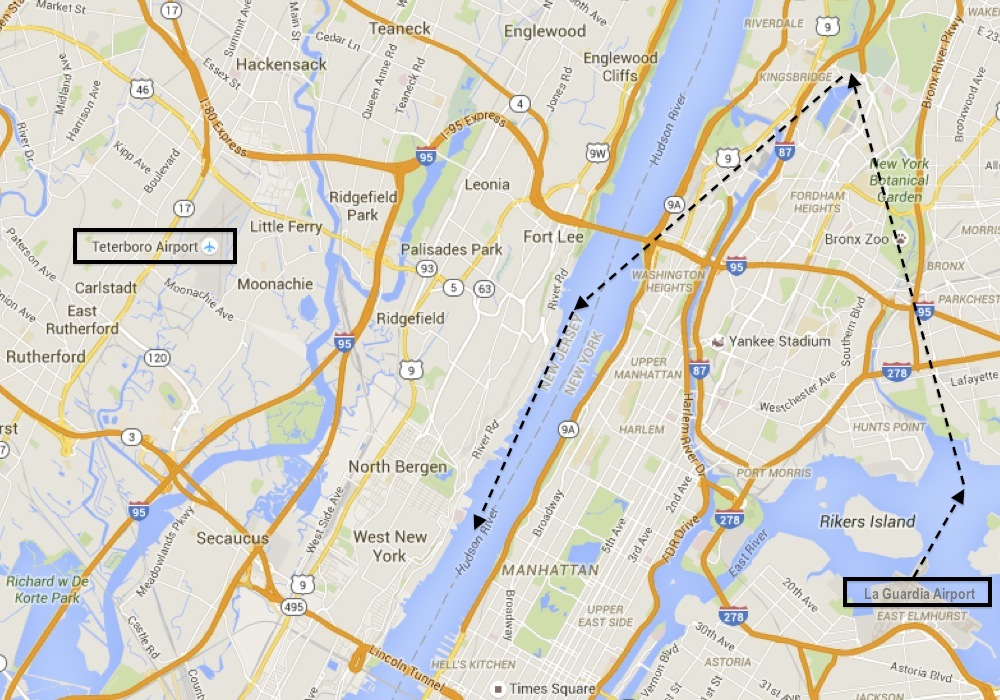

(Map of the flight’s approximate path showing the two airports)

Waiting on the wings

By all accounts, Flight 1549 made the perfect landing: wings level, nose up, speed at just above the minimum. The river, though, had sliced through the plane’s rear section and was filling it fast with water. Exiting the cockpit, the pilots gave the order to evacuate, and flight attendants Donna Dent, Doreen Welsh and Sheila Dail organized an orderly evacuation at the front doors and over the wings. Although most didn’t put on their life vests, the passengers helped each other move to the front of the plane and out.

The photo is now iconic: the A320 floating on the water, its passengers and crew members balancing on its wings. The damaged plane itself would end up underwater, but all 155 occupants, including a 9-month-old boy, survived. What a view of the Hudson.

The reality of the aftermath – that some passengers panicked or slipped into the freezing water, or thought they were going to die after surviving the landing – was not captured on cameras or voice recordings. In 2014, a National Geographic film depicted their experience, showing that some were more traumatized than others. The same goes for the crew. When Welsh exited the plane, she realized a metal bar had cut into her leg, and she was bleeding from the mouth because she had bit down on her tongue upon impact. Flight 1549 was her last as a cabin attendant.

Nonetheless, what could have ended in tragedy became a thrilling feel-good story. In 2015, Clint Eastwood started filming the Hollywood version with Tom Hanks as Captain Sully. From bird strike to splashdown, only three and a half minutes had passed, so Sully’s quick thinking and decades of flying were absolutely critical. But more was at work that afternoon. A day later and the river would have been filled with chunks of ice. An hour forward, and they would have had to land in darkness. A less experienced co-pilot and cabin crew, and they might not have acted with such composure or in such balletic concert. Call these things luck, but New York’s then-governor gave it a more enduring name: the Miracle on the Hudson.

You Should Also Read:

Pilotwings Resort 3DS

Airplane! Movie Review

The Discovery of Ganymede

Related Articles

Editor's Picks Articles

Top Ten Articles

Previous Features

Site Map

Content copyright © 2023 by Lane Graciano. All rights reserved.

This content was written by Lane Graciano. If you wish to use this content in any manner, you need written permission. Contact Lane Graciano for details.