Brewing With Chris LaPierre - An Iron Hill Experience

Guy, Dave, Kevin, and I worked together…weird shifts, rotating hours, detail, attention, and just enough time to catch a few zzz’s before we were back at it again. This was the world of magazines, years before computers could make our lives easy - a laborious mind-game that needed release when rest finally came. We were young adults - smart, physical, and full of unrestrained courage.

We thought spelunking would be a great idea, and there happened to be a few caves that begged exploration in the nearby mountains. There were skills among us. Some had rappelled; one was a balloonist; this Fox could control a canoe. We had equipment that served as a catch-all of sorts – harnesses, ascenders, portable boats, flashlights, and pickup trucks – and no sense of fear. Out in the wilderness, it made sense for me to go in first. I had the smallest physical stature - the girl who could shimmy into just about any little black opening with flashlight-in-hand.

The perks were clear. I would get to see the interior first – the magnificent vaulted ceiling, stalagmites, and pools of water that led to secret underground coves. The thought of a confrontation with snakes or bats was ever-present, but the feeling of accomplished reward far outweighed any fear that may have lingered in my subconscious mind. It was satisfying to explore the unknown and to delve into a craft that held a sense of mystery. That feeling never changes. When Chris LaPierre of Iron Hill Restaurant & Brewery invited me to “guest brew” with him at his brewhouse in West Chester, Pennsylvania, that surge of excitement came rushing back into my veins. How many brewers had I observed, working the mash, with billows of steam encircling them, reminiscent of a Turner painting? That aroma of fresh grain - sweet, biscuity, bready, and rich! The crackle of papery hops that could reduce me to the actions of a feline on a bed of catnip!

That feeling never changes. When Chris LaPierre of Iron Hill Restaurant & Brewery invited me to “guest brew” with him at his brewhouse in West Chester, Pennsylvania, that surge of excitement came rushing back into my veins. How many brewers had I observed, working the mash, with billows of steam encircling them, reminiscent of a Turner painting? That aroma of fresh grain - sweet, biscuity, bready, and rich! The crackle of papery hops that could reduce me to the actions of a feline on a bed of catnip!

I had interviewed the “Brew-Girls” at the Great American Beer Festival. Such inspiration made me jump at the opportunity to wear the coveted pink boots. Okay, mine were really a pair of non-slip athletic shoes, but let’s not quibble about details. I was dressed and ready to rock!

Chris LaPierre loves his work, and can’t wait to share its secrets with other interested enthusiasts. Although he graduated from Syracuse University with a degree in Journalism, he was bitten by the brewing-bug as a homebrewer in college. He continued to cultivate his interest while working in a brewpub where he volunteered as an apprentice brewer. His first brewing job was at the original Dock Street Brewery at 18th and Cherry in the great beer-city of Philadelphia. “Being a brewer appealed to me because it mixes hands-on with using your mind,” he says. “It’s nice to make something – to point to something and see people drinking it, and enjoying it.” As with most brewers, LaPierre went where his experience could expand, following his nose to Harpoon Brewing in Boston, Massachusetts, where he was commissioned to attend Siebel Institute of Brewing Technology in Chicago. He eventually returned to Philadelphia, and was quickly landed by Iron Hill, who sent him for six additional months of education at the American Brewers Guild.  Chris never flaunts his knowledge, but throughout the day, it becomes clear that brewing holds more complexity than the simple phrase “It’s both an art and a science.”

Chris never flaunts his knowledge, but throughout the day, it becomes clear that brewing holds more complexity than the simple phrase “It’s both an art and a science.”

We were making a Winter Warmer, a full-bodied, spiced beer that would ring-in the Holiday season and warm the spirit on a snowy evening. My mind filled with visions of popping cherry-wood in the fireplace, cinnamon sticks tied with gingham fabric, dancing eyes filled with laughter, and chocolate…lots of chocolate. This brew would be the perfect elixir for just such a night.

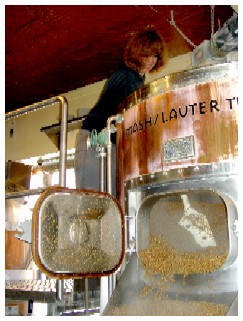

The complexity of such a beer is astounding. Iron Hill mills the malt at the time it is needed for brewing, ensuring the grain will retain its fresh character. Fifty-five pound sacks of grain are slit open above a stainless hopper, where they are milled to perfection – some grains are cracked, while others are left with the husks intact for effective filtering purposes. My notes indicate that we used a variety of tasty malts. Brewmaster LaPierre encouraged me to investigate the sensory differences of each malt by aroma and taste – Pilsner and Munich malt, with their bready, biscuity profiles; Caramel malt with a touch of sweetness; Black malt, with flavors of roasted coffee and tobacco; Chocolate malt, displaying the light, smooth layers of unsweetened baker’s chocolate; and Vienna malt, with a delicate touch of doughy sweetness. Malt dust can have a high degree of lactobacillus in it, which can contribute to a sour mash, so the milling is done in a separate room, away from brewing operations. The experienced brewer will take note of the surroundings and set up the brewhouse with this in mind. We then transferred the milled grain into the sanitized mash tun, where I helped hand mix it with water, avoiding clumps that resulted in a thick porridge-like substance. Chemicals were added at this stage to adjust water chemistry, and the mash was held at ideal temperature settings that would break down more complex sugars into simple sugars to complement the requirements of the selected yeast. Minerals and nutrients may also be added at this point. Irish Moss is often used to help protein coagulate. Some brewers use high tech plastics that achieve coagulation on the principle of static electricity. Yeast nutrients (such as servomyces) may be added to raise the zinc level and provide a healthy environment for yeast.

We then transferred the milled grain into the sanitized mash tun, where I helped hand mix it with water, avoiding clumps that resulted in a thick porridge-like substance. Chemicals were added at this stage to adjust water chemistry, and the mash was held at ideal temperature settings that would break down more complex sugars into simple sugars to complement the requirements of the selected yeast. Minerals and nutrients may also be added at this point. Irish Moss is often used to help protein coagulate. Some brewers use high tech plastics that achieve coagulation on the principle of static electricity. Yeast nutrients (such as servomyces) may be added to raise the zinc level and provide a healthy environment for yeast.

After an hour, we began to pump hot water into the mash, collecting the wort and recirculating, or vorlaufing, this sweet liquid through the grain bed. This makes the wort more robust, transferring a greater percentage of available sugars from the grain bed into the sweet wort for brewing. The wort was then transferred to the Brewkettle, where we added Northern Brewer Hops for bittering at the beginning of the brewing cycle.

A rolling boil for an hour or more in the brewkettle was necessary to bind hop compounds to polypeptides. This forms colloids that remain in the beer, and aids in the formation of a good, stable head. A rolling boil kills bacteria, fungi and wild yeast, and stops enzymatic action. Undesirable volatile compounds are also removed in this step, as well as harsh hop compounds, esters and sulphur compounds.  In the meantime, I began shoveling the spent grain from the mash tun. We filled nearly five large containers with grain, which will be used as feed for cattle. We hosed down and cleaned the brewhouse floor, and visited the cask cellar. LaPierre took a sample of the yeast we were to use for our Winter Warmer, and put it under the microscope. We viewed mother cells, baby cells and sister cells, and discussed yeast cycles and the way they reproduce and multiply.

In the meantime, I began shoveling the spent grain from the mash tun. We filled nearly five large containers with grain, which will be used as feed for cattle. We hosed down and cleaned the brewhouse floor, and visited the cask cellar. LaPierre took a sample of the yeast we were to use for our Winter Warmer, and put it under the microscope. We viewed mother cells, baby cells and sister cells, and discussed yeast cycles and the way they reproduce and multiply.

Just before the end of the boil, the brewer will usually add hops for flavoring and aroma. Since we were brewing a spiced "Warmer," we added a secret bouquet of spices rather than additional hops. After a mere five minutes, we began to transfer our solution to the sanitized fermenter, adding healthy, lively yeast for the final step of fermentation. Like a mother hen, I wanted to sit by the fermenter and wait for my chicks to hatch. Good beer takes time, and Chris assured me that his record-keeping would monitor our Winter Warmer and ensure that it moved along with finesse.  I am amazed at the level of physics involved. Pumps, hoses, heat exchangers, nuts, bolts and electrical panels all take a position of prominence for the brewer. The brewer also needs to understand biology, chemistry, botany, and sensory perception, while using the creativity of Einstein and the complex combined artistry of Peter Paul Reubens and Ralph Steadman. There is little “down-time.”

I am amazed at the level of physics involved. Pumps, hoses, heat exchangers, nuts, bolts and electrical panels all take a position of prominence for the brewer. The brewer also needs to understand biology, chemistry, botany, and sensory perception, while using the creativity of Einstein and the complex combined artistry of Peter Paul Reubens and Ralph Steadman. There is little “down-time.”

While waiting for each cycle to complete, we were measuring and recording specific gravity or degrees plato, selecting ingredients, keeping records, hooking up pumps, cleaning, and sanitizing equipment. I now know why brewers wear knee-high rubber boots and elbow-length rubber gloves. With pink brewer's boots, I would have escaped the water that slowly absorbed into my pants from the bottom cuffs.

Of course, I consider this bit of wetness my badge of honor signifying the rich experience of brewing a batch of Winter Warmer. In approximately three weeks, our beer will be calling for attention, mature and ready for holiday celebrations. In my writer's mind, I can already taste the zesty spiciness on my tongue, even before it pours into my glass. I can recall the rich malty aromas of the brewpub, and look forward to the lively pleasures that await me in my next gustatory adventure.

Cheers!

You Should Also Read:

Women Brewmasters - Inside the Brewers' Studio

Homebrewing - Books & Resources - Novice to Expert

The Elite Pride of Women Brewers

Related Articles

Editor's Picks Articles

Top Ten Articles

Previous Features

Site Map

Content copyright © 2023 by Carolyn Smagalski. All rights reserved.

This content was written by Carolyn Smagalski. If you wish to use this content in any manner, you need written permission. Contact Carolyn Smagalski for details.