John Herschel

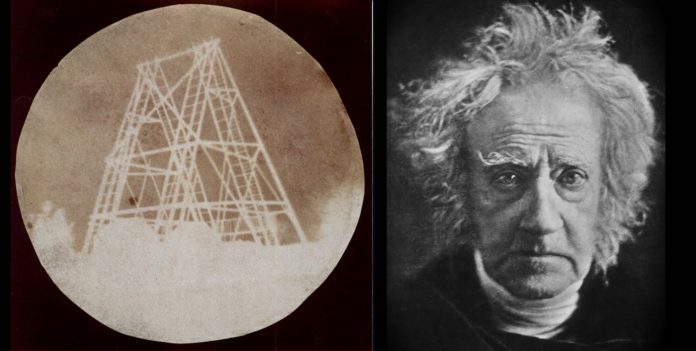

John Herschel took the photo of his father's 40-foot telescope when it was being dismantled. A photograph of John Herschel himself was taken by Julia Margaret Cameron. [Good News Network]

It's not easy for the son of a famous father to make his own reputation. John Herschel's father William (1738-1822) was the first person in history to discover a new planet. But John Herschel wasn't interested in fame, yet became one of the 19th century's most distinguished individuals.

Early life

John Frederick William Herschel was the only child of William Herschel and Mary Baldwin Pitt. Born in Slough, England on March 7, 1792, he was educated at a local school, Later he was at Eton until his mother withdrew him because he was being bullied. A private tutor was then hired to teach him at home, and later to prepare him for the Cambridge University entrance exam.

John was 17 when he attended St John's College, Cambridge where he studied mathematics. At the end of his degree studies, he earned the top marks in the fiendishly difficult math exam that determined who was the “Senior Wrangler” for that year. This was a long-standing tradition at the university and a highly prestigious accomplishment.

But even before completing his degree, Herschel had submitted a mathematical paper to the Royal Society (Britain's premier scientific society). He was elected to the society in 1813, one of their youngest ever members.

Despite his interest in mathematics and science, Herschel oddly decided on a law career. But a year and a half of that changed his mind, and sent him back to Cambridge to be a math tutor.

But math wasn't his only accomplishment. He was a highly competent musician, artist and linguist. He helped to translate a French book on mathematics into English, and in later years would translate the German poet Schiller into both English and Latin, and Homer's Iliad into English verse.

Astronomy

Although John Herschel liked chemistry, and light and optics, he seemed to avoid astronomy. Perhaps he didn't want to compete with his father. Yet eventually he was drawn into it by his friend James South, and the realization that his father needed him. In his late seventies, William Herschel's passion for astronomy was unflagging, but not his health.

William and John rebuilt the 20-foot reflecting telescope which had been used for a survey of 2500 nebulae of the northern skies. When William died in 1822, the task of extending the nebula survey to the southern skies was a commitment that John said was not “a matter of choice or taste, but a sacred duty.”

John Herschel was a co-founder of the Royal Astronomical Society, and later served three terms as its president.

In 1829, John married Margaret Brodie Stewart who was nearly twenty years his junior. A lovely, charming, intelligent young woman, she was also a talented artist and musician. It was a happy marriage which produced twelve children, all of whom survived to adulthood, which was unusual in that era.

Cape of Good Hope

The southern skies beckoned, and in 1833 John, Margaret, three small children, nannies, and a selection of telescopes sailed to what is now Cape Town, South Africa. John reckoned the five years they spent there as among the happiest of his life.

They set up home and an observatory on a property called Feldhausen. It's now a school in a suburb of Cape Town where an obelisk marks the site of the 20-foot telescope.

John carried out a prodigious observing program at Feldhausen. Thomas Maclear, a friend from England, was the director of the Royal Observatory in Cape Town. Not only did the two astronomers consult each other from time to time, but the families also socialized. Herschel took an active part in local life, and is credited with helping to lay the foundations for education in South Africa.

When the Herschels returned to England in 1838, it was with six children, thousands of careful astronomical observations, and a large number of illustrations of the local flora made by John and Margaret.

Herschel's scientific work

John Herschel published over 150 scientific papers. Many related to astronomy, but he also contributed to other areas, including mathematics, chemistry and meteorology. His Discourse on Natural Philosophy was a thoughtful look at the practice of scientific inquiry. What we call science today was known as natural philosophy in those days.

John Herschel was also a pioneer of photography. His most important contribution was the experimentation that led to his finding that hyposulphite of soda would fix the photograph so that it didn't fade. “Hypo” was a great step forward for photography. He also invented the cyanotype process, better known as "blueprints". More interested in advancing science than advancing himself, Herschel freely shared his discoveries and wasn't concerned that sometimes others took the credit.

Honors

Herschel's comfortable inheritance from his mother let him work independently. Beyond the early tutoring at Cambridge, his only paid employment was a few years as Master of the Mint. That job didn't suit him and he resigned when his health suffered.

Many scientific honors came Herschel's way. And he was knighted by King William IV and made a baronet by Queen Victoria. When Sir John Herschel died on May 11, 1872, there was a service in Westminster Abbey, and he was laid to rest near Sir Isaac Newton.

It's not easy for the son of a famous father to make his own reputation. John Herschel's father William (1738-1822) was the first person in history to discover a new planet. But John Herschel wasn't interested in fame, yet became one of the 19th century's most distinguished individuals.

Early life

John Frederick William Herschel was the only child of William Herschel and Mary Baldwin Pitt. Born in Slough, England on March 7, 1792, he was educated at a local school, Later he was at Eton until his mother withdrew him because he was being bullied. A private tutor was then hired to teach him at home, and later to prepare him for the Cambridge University entrance exam.

John was 17 when he attended St John's College, Cambridge where he studied mathematics. At the end of his degree studies, he earned the top marks in the fiendishly difficult math exam that determined who was the “Senior Wrangler” for that year. This was a long-standing tradition at the university and a highly prestigious accomplishment.

But even before completing his degree, Herschel had submitted a mathematical paper to the Royal Society (Britain's premier scientific society). He was elected to the society in 1813, one of their youngest ever members.

Despite his interest in mathematics and science, Herschel oddly decided on a law career. But a year and a half of that changed his mind, and sent him back to Cambridge to be a math tutor.

But math wasn't his only accomplishment. He was a highly competent musician, artist and linguist. He helped to translate a French book on mathematics into English, and in later years would translate the German poet Schiller into both English and Latin, and Homer's Iliad into English verse.

Astronomy

Although John Herschel liked chemistry, and light and optics, he seemed to avoid astronomy. Perhaps he didn't want to compete with his father. Yet eventually he was drawn into it by his friend James South, and the realization that his father needed him. In his late seventies, William Herschel's passion for astronomy was unflagging, but not his health.

William and John rebuilt the 20-foot reflecting telescope which had been used for a survey of 2500 nebulae of the northern skies. When William died in 1822, the task of extending the nebula survey to the southern skies was a commitment that John said was not “a matter of choice or taste, but a sacred duty.”

John Herschel was a co-founder of the Royal Astronomical Society, and later served three terms as its president.

In 1829, John married Margaret Brodie Stewart who was nearly twenty years his junior. A lovely, charming, intelligent young woman, she was also a talented artist and musician. It was a happy marriage which produced twelve children, all of whom survived to adulthood, which was unusual in that era.

Cape of Good Hope

The southern skies beckoned, and in 1833 John, Margaret, three small children, nannies, and a selection of telescopes sailed to what is now Cape Town, South Africa. John reckoned the five years they spent there as among the happiest of his life.

They set up home and an observatory on a property called Feldhausen. It's now a school in a suburb of Cape Town where an obelisk marks the site of the 20-foot telescope.

John carried out a prodigious observing program at Feldhausen. Thomas Maclear, a friend from England, was the director of the Royal Observatory in Cape Town. Not only did the two astronomers consult each other from time to time, but the families also socialized. Herschel took an active part in local life, and is credited with helping to lay the foundations for education in South Africa.

When the Herschels returned to England in 1838, it was with six children, thousands of careful astronomical observations, and a large number of illustrations of the local flora made by John and Margaret.

Herschel's scientific work

John Herschel published over 150 scientific papers. Many related to astronomy, but he also contributed to other areas, including mathematics, chemistry and meteorology. His Discourse on Natural Philosophy was a thoughtful look at the practice of scientific inquiry. What we call science today was known as natural philosophy in those days.

John Herschel was also a pioneer of photography. His most important contribution was the experimentation that led to his finding that hyposulphite of soda would fix the photograph so that it didn't fade. “Hypo” was a great step forward for photography. He also invented the cyanotype process, better known as "blueprints". More interested in advancing science than advancing himself, Herschel freely shared his discoveries and wasn't concerned that sometimes others took the credit.

Honors

Herschel's comfortable inheritance from his mother let him work independently. Beyond the early tutoring at Cambridge, his only paid employment was a few years as Master of the Mint. That job didn't suit him and he resigned when his health suffered.

Many scientific honors came Herschel's way. And he was knighted by King William IV and made a baronet by Queen Victoria. When Sir John Herschel died on May 11, 1872, there was a service in Westminster Abbey, and he was laid to rest near Sir Isaac Newton.

You Should Also Read:

Royal Observatory Cape of Good Hope

Caroline Herschel

Herschel Partnership - for Kids

Related Articles

Editor's Picks Articles

Top Ten Articles

Previous Features

Site Map

Content copyright © 2023 by Mona Evans. All rights reserved.

This content was written by Mona Evans. If you wish to use this content in any manner, you need written permission. Contact Mona Evans for details.