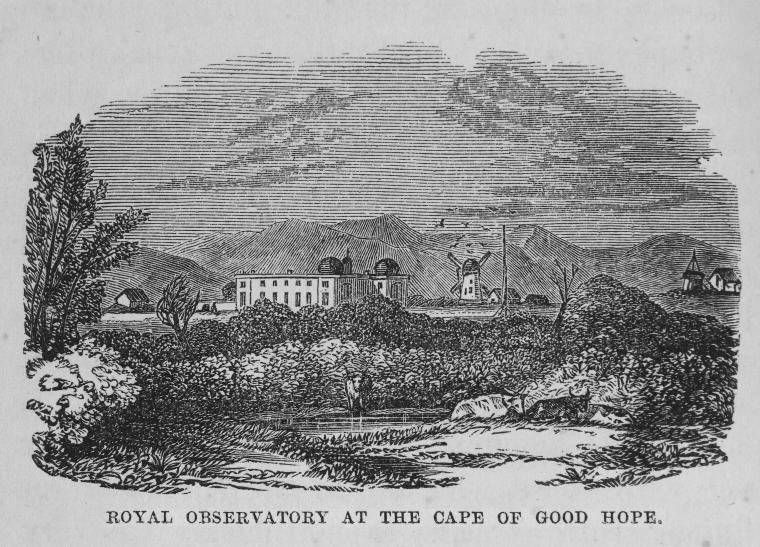

Royal Observatory Cape of Good Hope

In 1820, when the Royal Observatory was founded the bright lights of Cape Town didn't exist. But by 1972 urbanization had greatly changed the Cape of Good Hope and the Royal Observatory merged with Johannesburg's Republic Observatory to form the South African Astronomical Observatory (SAAO). The SAAO's headquarters are in the grounds of the former Royal Observatory, but the research telescopes are in a dark sky site well away from the city.

The observatory site

The observatory borders the Two Rivers Urban Park, a conservation area a few miles from the city center. Here the original ecology of the area is preserved – a wetland with a variety of animal life and plants. The Royal Observatory was built on a low hill visible from Table Bay.

A pleasant drive through a wooded site takes you to the main building. Dating from 1828, this was the original building of the Royal Observatory. Neo-classical in style, it faces a large lawn and seems to preside over the newer Victorian buildings. The wings once accommodated Her Majesty's Observer – as the director was styled – and senior staff. The central area was for observing.

Today the building houses the National Library for Astronomy. The original teak floors, window frames and shutters, as well as a number of other historic features, have been retained. Some parts of the building are now offices.

The McClean telescope dome and laboratory, built in 1896, is used mainly as a museum and visitor's center. An interesting feature of the dome is a floor that can be raised hydraulically, using its original motor. The telescope is used for public open evenings.

An observatory at the tip of Africa

We might well wonder why an observatory would be a high priority for a fairly new colony eight thousand miles from home. But it was built for commercial and military reasons. The Cape of Good Hope was strategically located on the route to the Indian Ocean and it was a busy port. Its observatory was to be the southern equivalent of the Royal Observatory at Greenwich, surveying the southern skies to provide accurate navigational information, and providing a time check for ships.

In the days before GPS, the key to finding your longitude at sea was timekeeping. The clocks of the day weren't as precise and reliable as the ones we're used to. And if the clock was wrong, you could be way off course.

The Royal Observatory at Greenwich gave ships a time check using a time ball. This is a large colorful ball on a pole, visible from a distance, which drops at a specified time – 1:00 at Greenwich.

The observatory at the Cape of Good Hope was built in sight of Table Bay in order to give a time signal to ships in the harbor. One Observer used to stand on the observatory roof with a flare pistol, but his successor used a time ball. Yet as the town grew, ships couldn't see the observatory any more, so the system incorporated a big gun on Signal Hill. There is still a noon gun in modern Cape Town, and it's triggered remotely from the observatory.

By the end of the nineteenth century, new technology made it possible to have time balls at more than one location, all triggered by a signal from the observatory. Today's visitors to the Victoria and Alfred waterfront can see the restored tower and time ball which was built there in 1894.

Some historical highlights

The Royal Observatory was the first permanent modern observatory in the southern hemisphere and it accomplished a great deal in charting the southern skies, as well as other contributions to astronomy.

Fearon Fallows (1788-1831) was the man with the unenviable task of building the observatory. Local conditions were difficult, and materials and skilled workmen scarce. He also suffered from unhelpful officials in England, not to mention the sort of bureaucratic ineptitude that mislaid the architect's plans for three years. It took nearly eight years to get the observatory into operation and even then he had to work with instruments requiring two people, but without an assistant. Fortunately, his wife Mary Ann proved to be quite able, and she even discovered a comet one night.

Fallows was 42 when he died of scarlet fever. He's buried in the observatory grounds.

Thomas Henderson (1798-1844) was Fallows's successor. He loathed the place, calling it a “dismal swamp”, and stayed just over a year. Yet in that time he measured the positions of nearly ten thousand stars and made the observations which later let him later calculate the distance to Alpha Centauri. He didn't publish his results immediately, so the credit for being first to work out the distance to a star went elsewhere.

Thomas Maclear (1794-1879) ran the observatory from 1834-1870. He did extensive observations, helped in his efforts to improve the observatory by his friend John Herschel. Herschel spent five years in the area observing the southern skies. Maclear's wife Mary died in 1861 and was buried in the observatory grounds. Eighteen years later, he was buried beside her.

In the last quarter of the 19th century the observatory was chiefly a research institution. The prime mover in modernizing it into a world-class facility was David Gill, the Observer from 1879 – 1907. One of his many accomplishments was making the first systematic sky survey using photography.

Visiting

School and other groups can arrange for tours during the day, and daytime visits may include looking at sunspots. The twice-monthly evening events include a lecture, a visit to the museum and library, and viewing through a telescope, weather permitting. The facilities are also used for conferences and courses.

The observatory site

The observatory borders the Two Rivers Urban Park, a conservation area a few miles from the city center. Here the original ecology of the area is preserved – a wetland with a variety of animal life and plants. The Royal Observatory was built on a low hill visible from Table Bay.

A pleasant drive through a wooded site takes you to the main building. Dating from 1828, this was the original building of the Royal Observatory. Neo-classical in style, it faces a large lawn and seems to preside over the newer Victorian buildings. The wings once accommodated Her Majesty's Observer – as the director was styled – and senior staff. The central area was for observing.

Today the building houses the National Library for Astronomy. The original teak floors, window frames and shutters, as well as a number of other historic features, have been retained. Some parts of the building are now offices.

The McClean telescope dome and laboratory, built in 1896, is used mainly as a museum and visitor's center. An interesting feature of the dome is a floor that can be raised hydraulically, using its original motor. The telescope is used for public open evenings.

An observatory at the tip of Africa

We might well wonder why an observatory would be a high priority for a fairly new colony eight thousand miles from home. But it was built for commercial and military reasons. The Cape of Good Hope was strategically located on the route to the Indian Ocean and it was a busy port. Its observatory was to be the southern equivalent of the Royal Observatory at Greenwich, surveying the southern skies to provide accurate navigational information, and providing a time check for ships.

In the days before GPS, the key to finding your longitude at sea was timekeeping. The clocks of the day weren't as precise and reliable as the ones we're used to. And if the clock was wrong, you could be way off course.

The Royal Observatory at Greenwich gave ships a time check using a time ball. This is a large colorful ball on a pole, visible from a distance, which drops at a specified time – 1:00 at Greenwich.

The observatory at the Cape of Good Hope was built in sight of Table Bay in order to give a time signal to ships in the harbor. One Observer used to stand on the observatory roof with a flare pistol, but his successor used a time ball. Yet as the town grew, ships couldn't see the observatory any more, so the system incorporated a big gun on Signal Hill. There is still a noon gun in modern Cape Town, and it's triggered remotely from the observatory.

By the end of the nineteenth century, new technology made it possible to have time balls at more than one location, all triggered by a signal from the observatory. Today's visitors to the Victoria and Alfred waterfront can see the restored tower and time ball which was built there in 1894.

Some historical highlights

The Royal Observatory was the first permanent modern observatory in the southern hemisphere and it accomplished a great deal in charting the southern skies, as well as other contributions to astronomy.

Fearon Fallows (1788-1831) was the man with the unenviable task of building the observatory. Local conditions were difficult, and materials and skilled workmen scarce. He also suffered from unhelpful officials in England, not to mention the sort of bureaucratic ineptitude that mislaid the architect's plans for three years. It took nearly eight years to get the observatory into operation and even then he had to work with instruments requiring two people, but without an assistant. Fortunately, his wife Mary Ann proved to be quite able, and she even discovered a comet one night.

Fallows was 42 when he died of scarlet fever. He's buried in the observatory grounds.

Thomas Henderson (1798-1844) was Fallows's successor. He loathed the place, calling it a “dismal swamp”, and stayed just over a year. Yet in that time he measured the positions of nearly ten thousand stars and made the observations which later let him later calculate the distance to Alpha Centauri. He didn't publish his results immediately, so the credit for being first to work out the distance to a star went elsewhere.

Thomas Maclear (1794-1879) ran the observatory from 1834-1870. He did extensive observations, helped in his efforts to improve the observatory by his friend John Herschel. Herschel spent five years in the area observing the southern skies. Maclear's wife Mary died in 1861 and was buried in the observatory grounds. Eighteen years later, he was buried beside her.

In the last quarter of the 19th century the observatory was chiefly a research institution. The prime mover in modernizing it into a world-class facility was David Gill, the Observer from 1879 – 1907. One of his many accomplishments was making the first systematic sky survey using photography.

Visiting

School and other groups can arrange for tours during the day, and daytime visits may include looking at sunspots. The twice-monthly evening events include a lecture, a visit to the museum and library, and viewing through a telescope, weather permitting. The facilities are also used for conferences and courses.

You Should Also Read:

Royal Observatory Greenwich

Photography and the Birth of Astrophysics

Caroline Herschel

Related Articles

Editor's Picks Articles

Top Ten Articles

Previous Features

Site Map

Content copyright © 2023 by Mona Evans. All rights reserved.

This content was written by Mona Evans. If you wish to use this content in any manner, you need written permission. Contact Mona Evans for details.