Robert Hooke - England's Leonardo

Robert Hooke (1635-1703) isn't a well known name. Yet in the 17th century he was the author of a groundbreaking best-selling book and a renowned scientific experimenter. He was also a prominent architect and surveyor, working with his friend Christopher Wren to rebuild London after the Great Fire of 1666.

Although I'm writing about Hooke because he was an astronomer, his life could be equally relevant to someone interested in the history of microbiology, geology, evolutionary biology, structural engineering, physics or chemistry. If I add that Hooke was also an inventor, a musician and a talented artist, you'll understand why he's been dubbed England's Leonardo.

Family and education

Born in Freshwater, Isle of Wight in southern England, Robert was the son of John Hooke, a curate and schoolteacher. Robert was a sickly child, so rather than being sent to school as his brothers had been, he was home-educated until his father fell ill. After that he was pretty much self-educated, which worked well as he was an inquisitive child who liked to observe nature. He also not only liked mechanical devices, but was good at making them. He showed such artistic talent that when his father died, the family arranged to send Robert to London as an artist's apprentice.

However the apprenticeship didn't suit Robert, and he felt that he needed to go to school. Richard Busby (1606–1695), the headmaster of Westminster School, recognized the teenager's genius and accepted him as a student and encouraged his self-guided learning. Robert took to mathematics like a duck to water, working through the first six volumes of Euclid's Elements in a week. Other subjects of note were mechanics, Latin and Greek, and learning to play the organ. When it seemed he'd learned all that he wanted at school, he got a place at Oxford University.

Oxford was the gathering place for the scientific intelligentsia of the time. There were scientists there who would become the the nucleus of the Royal Society in 1660. There was no family money for Hooke, but he had a scholarship and later worked as an assistant to Robert Boyle, the father of modern chemistry.

The Royal Society

The oldest scientific learned society still in existence had no name at the outset, but by the time Charles II granted it a royal charter in 1663, it was the The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge. No funding came with the charter, but the members were gentlemen of means and financed it through subscriptions and donations.

The charter provided for a curator of experiments and Hooke was the obvious choice. He was a superb experimenter, and accepted the job even though he didn't get a salary for some while. At least he did get elected to the society and was excused the annual fees. Eventually a salary did come, and also the post of Gresham Professor of Geometry. Besides a stipend, the latter came with rooms in Gresham College where Hooke lived for the rest of his life.

Micrographia

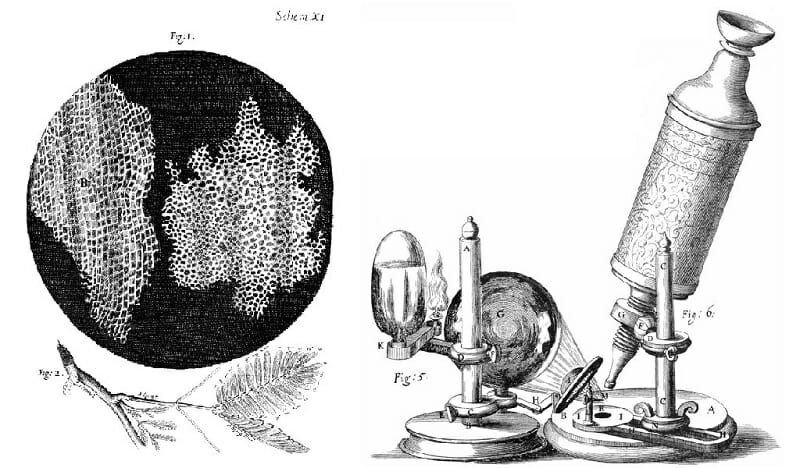

Hooke's book Micrographia shared what his microscope had revealed. The microscopic world was an even more amazing revelation than the heavens exposed by the telescope. The public, as well as scientists, looked at Hooke's drawings in wonderment. Diarist Samuel Pepys called it "the most ingenious book that I ever read in my life." And it wasn't just microscopic observations, for Hooke also included drawings and discussions about such things as planets, the wave theory of light, and fossils.

The header image is a drawing of Hooke's microscope in which he first saw cells in a thin slice of cork. [biologydictionary.net]

Surveying and architecture

Academia provided a bare subsistence, but surveying and architecture made him a living. Hooke was the City Surveyor of London for many years, and chief assistant to his friend Christopher Wren in rebuilding London after the Great Fire. Only a few of Hooke's buildings still exist, though the monument to the fire, which was substantially Hooke's work, is still there. As City Surveyor, Hooke was well-regarded by Londoners for his competence and scrupulous fairness.

Bitter and twisted?

Hooke's contemporary biographers certainly didn't do him any favors. One described him as “very crooked”. This didn't refer to his character, but to the spinal curvature that began when he was fifteen and worsened during his lifetime. He was also presented as bitter, resentful, anti-social and argumentative. Oxford historian Allan Chapman suggests that it might have been true in his later years when he suffered from very poor health and had become embittered by life and some of his scientific colleagues, especially Isaac Newton. However Chapman points out that he was quite sociable, enjoying the coffee houses, and stayed on good terms with old friends like Boyle and Wren throughout his life.

Death

Robert Hooke was buried at St Helen's Bishopsgate, but we no longer know where his remains are. In the 19th century, his bones were among those moved in order to repair the floor. At some point they were reinterred in a common grave somewhere in North London. The church used to have a commemorative window for Hooke, but after it was destroyed by an IRA bomb in 1993, it was replaced with plain glass.

Portrait

There's no authenticated portrait of Hooke. A 1710 visitor to the Royal Society mentioned seeing portraits of Boyle and Hooke there. When the society moved to a new meeting place, Boyle's portrait survived the move, but Hooke's didn't. Using two contemporary descriptions of Hooke, in 2003 history painter Rita Greer created a portrait. We will probably never know how accurate it is.

Reference:

Allan Chapman, "England's Leonardo: Robert Hooke (1635-1703) and the art of experiment in Restoration England" https://www.roberthooke.org.uk/leonardo.htm

Although I'm writing about Hooke because he was an astronomer, his life could be equally relevant to someone interested in the history of microbiology, geology, evolutionary biology, structural engineering, physics or chemistry. If I add that Hooke was also an inventor, a musician and a talented artist, you'll understand why he's been dubbed England's Leonardo.

Family and education

Born in Freshwater, Isle of Wight in southern England, Robert was the son of John Hooke, a curate and schoolteacher. Robert was a sickly child, so rather than being sent to school as his brothers had been, he was home-educated until his father fell ill. After that he was pretty much self-educated, which worked well as he was an inquisitive child who liked to observe nature. He also not only liked mechanical devices, but was good at making them. He showed such artistic talent that when his father died, the family arranged to send Robert to London as an artist's apprentice.

However the apprenticeship didn't suit Robert, and he felt that he needed to go to school. Richard Busby (1606–1695), the headmaster of Westminster School, recognized the teenager's genius and accepted him as a student and encouraged his self-guided learning. Robert took to mathematics like a duck to water, working through the first six volumes of Euclid's Elements in a week. Other subjects of note were mechanics, Latin and Greek, and learning to play the organ. When it seemed he'd learned all that he wanted at school, he got a place at Oxford University.

Oxford was the gathering place for the scientific intelligentsia of the time. There were scientists there who would become the the nucleus of the Royal Society in 1660. There was no family money for Hooke, but he had a scholarship and later worked as an assistant to Robert Boyle, the father of modern chemistry.

The Royal Society

The oldest scientific learned society still in existence had no name at the outset, but by the time Charles II granted it a royal charter in 1663, it was the The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge. No funding came with the charter, but the members were gentlemen of means and financed it through subscriptions and donations.

The charter provided for a curator of experiments and Hooke was the obvious choice. He was a superb experimenter, and accepted the job even though he didn't get a salary for some while. At least he did get elected to the society and was excused the annual fees. Eventually a salary did come, and also the post of Gresham Professor of Geometry. Besides a stipend, the latter came with rooms in Gresham College where Hooke lived for the rest of his life.

Micrographia

Hooke's book Micrographia shared what his microscope had revealed. The microscopic world was an even more amazing revelation than the heavens exposed by the telescope. The public, as well as scientists, looked at Hooke's drawings in wonderment. Diarist Samuel Pepys called it "the most ingenious book that I ever read in my life." And it wasn't just microscopic observations, for Hooke also included drawings and discussions about such things as planets, the wave theory of light, and fossils.

The header image is a drawing of Hooke's microscope in which he first saw cells in a thin slice of cork. [biologydictionary.net]

Surveying and architecture

Academia provided a bare subsistence, but surveying and architecture made him a living. Hooke was the City Surveyor of London for many years, and chief assistant to his friend Christopher Wren in rebuilding London after the Great Fire. Only a few of Hooke's buildings still exist, though the monument to the fire, which was substantially Hooke's work, is still there. As City Surveyor, Hooke was well-regarded by Londoners for his competence and scrupulous fairness.

Bitter and twisted?

Hooke's contemporary biographers certainly didn't do him any favors. One described him as “very crooked”. This didn't refer to his character, but to the spinal curvature that began when he was fifteen and worsened during his lifetime. He was also presented as bitter, resentful, anti-social and argumentative. Oxford historian Allan Chapman suggests that it might have been true in his later years when he suffered from very poor health and had become embittered by life and some of his scientific colleagues, especially Isaac Newton. However Chapman points out that he was quite sociable, enjoying the coffee houses, and stayed on good terms with old friends like Boyle and Wren throughout his life.

Death

Robert Hooke was buried at St Helen's Bishopsgate, but we no longer know where his remains are. In the 19th century, his bones were among those moved in order to repair the floor. At some point they were reinterred in a common grave somewhere in North London. The church used to have a commemorative window for Hooke, but after it was destroyed by an IRA bomb in 1993, it was replaced with plain glass.

Portrait

There's no authenticated portrait of Hooke. A 1710 visitor to the Royal Society mentioned seeing portraits of Boyle and Hooke there. When the society moved to a new meeting place, Boyle's portrait survived the move, but Hooke's didn't. Using two contemporary descriptions of Hooke, in 2003 history painter Rita Greer created a portrait. We will probably never know how accurate it is.

Reference:

Allan Chapman, "England's Leonardo: Robert Hooke (1635-1703) and the art of experiment in Restoration England" https://www.roberthooke.org.uk/leonardo.htm

You Should Also Read:

Edmond Halley

Isaac Newton – His Life

Mary Somerville and the World of Science – book

Related Articles

Editor's Picks Articles

Top Ten Articles

Previous Features

Site Map

Content copyright © 2023 by Mona Evans. All rights reserved.

This content was written by Mona Evans. If you wish to use this content in any manner, you need written permission. Contact Mona Evans for details.