Frank Boon - Preservationist of Lambic Tradition

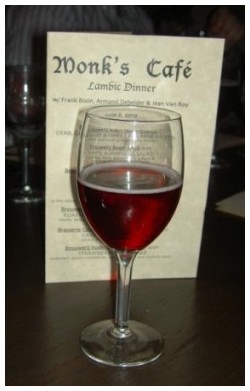

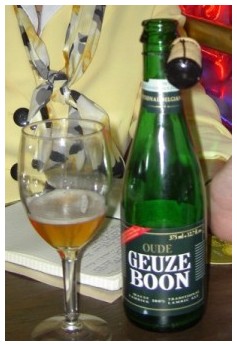

The rocky white head slathered my glass like clouds of meringue. I nosed the glass, enticed by the aroma of tart apple, lemon, and the dry cereal profile of whiskey, yet not as shockingly high in alcohol or hot to the nasal passages. An iridescent gold lit up my glass, and I sunk into the waves of flavor in this champagne of Brussels. Bold, yet softly acidic, the complex layers unrolled across my tongue - fruit drenched in vanilla, cork, and hints of clove. This was Boon (pronounced Bone) Oude Geuze, a style that was blessed by resurrection at the hands of its creator, Frank Boon.

The rocky white head slathered my glass like clouds of meringue. I nosed the glass, enticed by the aroma of tart apple, lemon, and the dry cereal profile of whiskey, yet not as shockingly high in alcohol or hot to the nasal passages. An iridescent gold lit up my glass, and I sunk into the waves of flavor in this champagne of Brussels. Bold, yet softly acidic, the complex layers unrolled across my tongue - fruit drenched in vanilla, cork, and hints of clove. This was Boon (pronounced Bone) Oude Geuze, a style that was blessed by resurrection at the hands of its creator, Frank Boon.

Oude Geuze echoed as an ingredient in the Crab Geuze and Sweet Pea Panna Cotta I was eating, adding a delicate profile to the rich base of crème fraiche. In following form, my eyes next drank in the soft pink head of Boon Kriek while its rich ruby body glimmered in my fingers. I sucked-in aromas of dark cherries, initially sweet, that gave way to wood, earth and almond. Effervescence tittered my tongue, while blended flavors, both sweet and tart, lingered well into the finish.

My eyes glanced across the room, seeking out the master, aware that my own Grand Finale to this Lambic dinner would be a personal interview with the virtuoso of Lambic beers. As an early champion of the style, Frank Boon appeared in the Burgundies of Belgium, one of the segments in Michael Jackson’s Beer Hunter Series of 1983.Waiting was unbearable, but my time finally arrived.  He was soft-spoken, yet intense. His dedication to tradition reflected in his eyes as he spoke about quality, consistency, and wild yeast. His story was one that merged history with life.

He was soft-spoken, yet intense. His dedication to tradition reflected in his eyes as he spoke about quality, consistency, and wild yeast. His story was one that merged history with life.

The World Exposition, also known as Exposition Universelle et Internationale de Bruxelles, opened in Brussels in 1958 where Stella Artois, a golden lager from Belgium, was its star in the footlights. Both Stella Artois, in its 24 year history, and cigarettes signaled “modern times,” while old style beers were a sign of the past. Lager was modern beer and the Belgian population wanted to be associated with it. They wanted to be seen as contemporary, chic, stylish. This movement was to flow into the Golden 60s, setting off a wave of closings among traditional Lambic breweries that would continue for two decades.

In the 1960s and 70s, these old-style Belgian breweries were closing at the rate of 10-15 per year. The locals were drinking lager, ambers and table beers. Table beers were about 0.8% alcohol, the result of a campaign in Belgium to curtail drinking among minors. Think about it … fruit juice, by its very nature, has nearly the alcoholic strength (between 0.3-0.4% ABV) as those table beers. Stella Artois had gained strength in the marketplace and sold so much beer at that time that 4 out of 10 beers sold were Stella. By 1968, one-third of the Lambic breweries in Belgium had closed. Frank Boon was a kid at the time, but was deeply influenced by a 1968 revolt in Paris, a student revolt against the big breweries. As was common in Belgium, Frank Boon came from a heritage of Belgian brewing. His family operated Ginder Brewery in Mirchtim, which closed its doors in the 1970s. They had brewed lagers, but competition from those large breweries took its toll. By 1975, Boon was working as a distributor of specialty beers and became acquainted with Rene DeVits, then 68, who ran the DeVits Brewery in the Zenne Valley. Rene was a bachelor with no heirs to assume his labor intensive Lambic brewhouse. This was an “old school” brewery, with a café, shop and brewery. DeVits said, “If I can only find someone to buy it …”

As was common in Belgium, Frank Boon came from a heritage of Belgian brewing. His family operated Ginder Brewery in Mirchtim, which closed its doors in the 1970s. They had brewed lagers, but competition from those large breweries took its toll. By 1975, Boon was working as a distributor of specialty beers and became acquainted with Rene DeVits, then 68, who ran the DeVits Brewery in the Zenne Valley. Rene was a bachelor with no heirs to assume his labor intensive Lambic brewhouse. This was an “old school” brewery, with a café, shop and brewery. DeVits said, “If I can only find someone to buy it …”

Frank Boon was a hard-core supporter of this “obsolete” style of brewing, and set his sights on owning the DeVits brewery. His family was skeptical. Ales ferment in 1-2 weeks, Lagers in 1-2 months, but this Lambic style required 2-3 years. How would he survive?

"Do what you want, but not a dime from us,” they warned. For two years he looked for other opportunities. He finally decided to sell the wholesale business to buy the old brewery from DeVits in 1977. He began blending his own Geuze and soon moved from the old brewery to a larger spot where he could brew 5 batches per year. At that time in 1977, he was producing 250 hl/year. His business grew and, by 2009, production had increased to 11,300 hl.  “To make it, you need to serve the customer,” said Boon, “and that is only done when the glass is empty.” With that in mind, he is meticulous about quality. “I have the largest laboratory of all the Lambeek breweries.”

“To make it, you need to serve the customer,” said Boon, “and that is only done when the glass is empty.” With that in mind, he is meticulous about quality. “I have the largest laboratory of all the Lambeek breweries.”

Brouwerij Frank Boon has lots of stainless steel, but it is actually second-hand. Two covers and one mash tun date from 1896. He told me of his plans to replace these in about a year to a vessel brewhouse, one that would give him three times the volume.

Two-hundred-two beers are made in 7 months, and all of that beer is fermented in cool ships, “the mailbox of the wild yeast,” he explained. The beer runs in at 7 pm, with about 8 million cells per mL, and by 6 o’clock in the morning, the yeast have multiplied to 30 million cells per mL. “Spontaneous fermentation is an amazing thing, but it works,” said Boon. “The Germans don’t think it’s possible, but we show them under a microscope. They don’t have as much wild yeast in Germany.”

The beer is only in cool ships overnight; then it is pumped into wooden casks. The oldest cask is from 1883. These casks are made of the best oak – over 200 years old. “You can’t find it anymore,” he said.

"Why?" I asked. Before WWI, production of Lambic Beer in Belgium hovered at approximately 1 million hectoliters per year. When the war broke out, casks used in the production of these beers were confiscated and used for sauerkraut. There were perhaps 3,300 Belgian casks before that first war, but afterwards, few were left – only about 1,600. During WWII, this number diminished even more, with only about 700 remaining at war’s end, but many 7,000 liter casks were eventually returned to Belgium as restitution. Frank Boon was fortunate to eventually become the owner of some of these huge casks. The brewery currently has 62 foeders, averaging 8,000 liters each, and over 200 smaller casks. Boon uses a turbid mashing system. This allows him to brew with 40% unmalted wheat. It also allows 42% of the wheat to get rid of the proteins in mashing, which produces more delicate beers with no strange smells and not too much acidity. The lambic is hop aged, mostly with Belgian varieties that have been dried and aged for over a year, allthough they may also use English, German, or Czech hops with low bitterness but good preservative qualities.

Boon uses a turbid mashing system. This allows him to brew with 40% unmalted wheat. It also allows 42% of the wheat to get rid of the proteins in mashing, which produces more delicate beers with no strange smells and not too much acidity. The lambic is hop aged, mostly with Belgian varieties that have been dried and aged for over a year, allthough they may also use English, German, or Czech hops with low bitterness but good preservative qualities.

The aim of the lambic brewer is to straddle the line between beer and wine, to make a champagne, of sorts, without too much acidity. “Sourness in Lambic should not surpass the sour in a glass of wine. That is a mistake,” he cautions.

As a starting point, he mirrored the style made by DeVits, then aimed for better. At first, only 20% was good, and then it became more consistent. “We wait until it freezes to brew. March is the best month for bottling.”

He speaks passionately about quality control. “I do the laboratory final control,” he said. “I do the tastings and the blendings. I do sensory analysis. I have standards.” Brouwerij Boon collaborates with the University of Leuven. This allows him to monitor many aspects of the beer they produce. He is aware that aging diminishes tastebuds and is careful to compare his own assessment with that done by the sensory specialists at the university. “Acidity is stronger for a young guy than for an older guy,” he noted. So he relies on the data from the university to control raw materials, flavor profiles, and wood from the casks. “We see the evolution of a beer as it ages from the Brett. Bruxellensis yeast is the most important yeast in lambic brewing. It can do different things at different temperatures. It’s a wild yeast, but can be predictable,” he asserts.

“We see the evolution of a beer as it ages from the Brett. Bruxellensis yeast is the most important yeast in lambic brewing. It can do different things at different temperatures. It’s a wild yeast, but can be predictable,” he asserts.

And predictable it is for Frank Boon. Boon Geuze Mariage Parfait and Boon Oude Geuze are the most difficult to create, the hardest to make consistent. But at the 2010 World Beer Cup Competition, Frank Boon won Gold and Silver medals, respectively, for both beers in the Belgian Style Sour Ale category. The World Beer Cup competition registered 3330 beers from 642 breweries in 44 countries.

Sales are growing for Boon, particularly in America. “Now there has been this big evolution due to absolutely well-informed brewers and lots of home brewers in the United States,” he said.

Frank Boon looks forward to having his son join in the business of brewing. He introduced his son to brewing when he was a little boy, not by taking him into the brewhouse, but by playing a game in which they made miniature breweries out of cardboard. Now his son is studying brewing. “It will be easier when my son goes into the brewery.”

We all should be so fortunate.

Cheers!

Photos are (from top): Frank Boon; Crab Geuze with Sweet Pea Panna Cotta & Boon Geuze; Boon Oude Geuze; Boon Kriek; Frank Boon & Jean Van Roy; Boon Oude Geuze in 75 cl bottle

You Should Also Read:

Rudi Ghequire & the Rodenbach Philosophy

Rodenbach 2007 Vintage Oak Aged Ale Barrel No. 230

Trappist Beer - The Select Seven

Related Articles

Editor's Picks Articles

Top Ten Articles

Previous Features

Site Map

Content copyright © 2023 by Carolyn Smagalski. All rights reserved.

This content was written by Carolyn Smagalski. If you wish to use this content in any manner, you need written permission. Contact Carolyn Smagalski for details.